Tommy Wilkins was the first to come to mind. Skinny kid with a stutter, started riding my bus in 1986. Every morning, he’d linger a few extra seconds to look at my bike parked in the school lot.

“Y-you ever g-going to let me s-sit on it, Mr. Ray?” he’d ask.

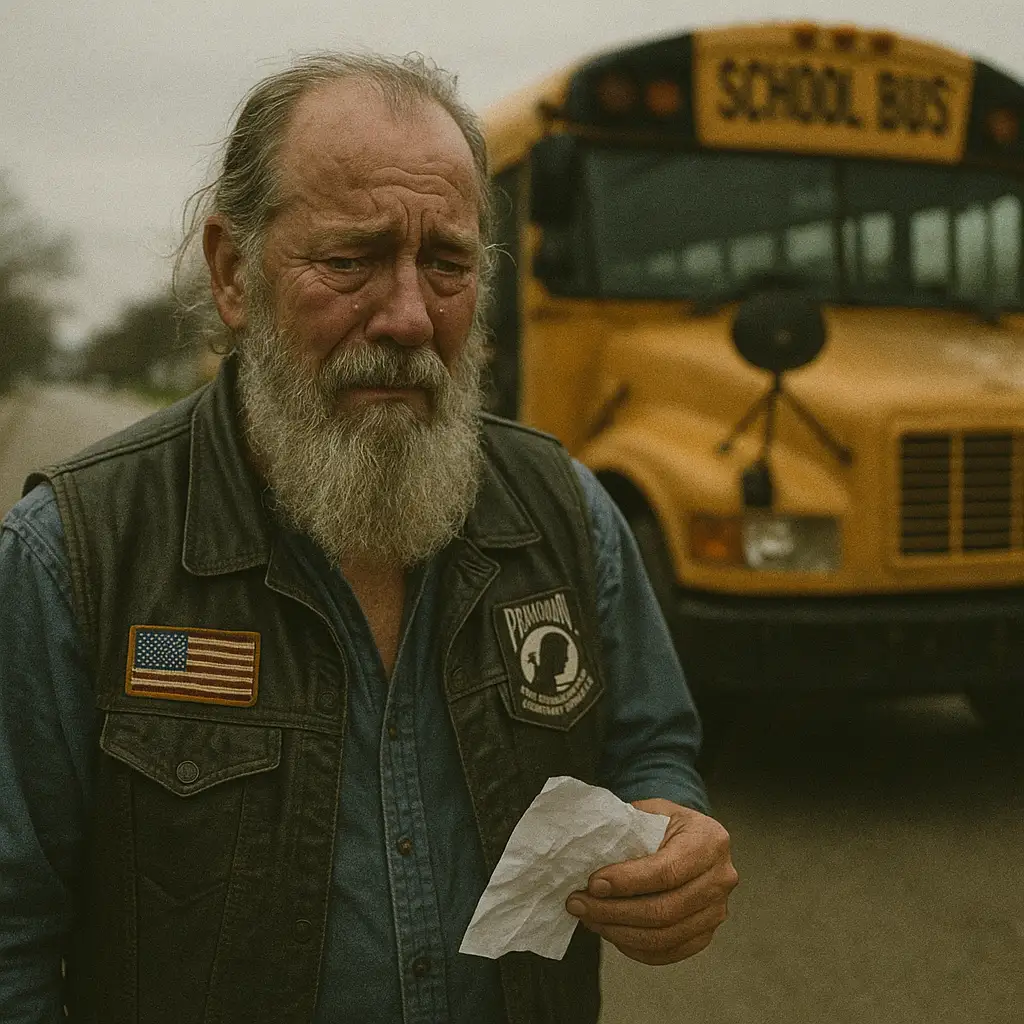

Tommy grew up, graduated, joined the Marines. Came back from his third tour in Afghanistan with haunted eyes and trembling hands. I ran into him at the grocery store one day, barely recognized the hollow-cheeked man as the boy who’d admired my bike.

“You still ride, Mr. Ray?” he’d asked, no stutter now, but something worse—a flatness, like he was speaking from underwater.

“Every Sunday,” I told him. “Weather permitting.”

That Sunday, he was waiting in my driveway at dawn, an old Sportster beneath him. We rode for hours, up into the mountains, not speaking, just riding. When we stopped for coffee, I noticed his hands weren’t shaking anymore.

For two years after that, Tommy rode with me every Sunday. Sometimes we talked, sometimes we didn’t. He told me once that the only time his mind quieted, the only time the memories stopped playing on repeat, was when he was on his bike.

“It’s like… the wind blows all the darkness away, just for a little while,” he’d said. “Lets me remember I’m still alive.”

Tommy was married now, with kids of his own. Still rode. Still called me “Mr. Ray.”

And there were others. Sarah Jenkins, who’d lost her husband and started riding his old Indian as a way to feel close to him. Dave Perkins from the auto shop, who’d been sober twenty years and swore riding saved his life when the bottle almost took it. My club brothers, most of them Vietnam vets who’d found on two wheels the peace that eluded them on four.